- When will AI surpass Facebook and Twitter as the major sources of fake news? – May 23, 2023

- The evolution of aging – May 7, 2023

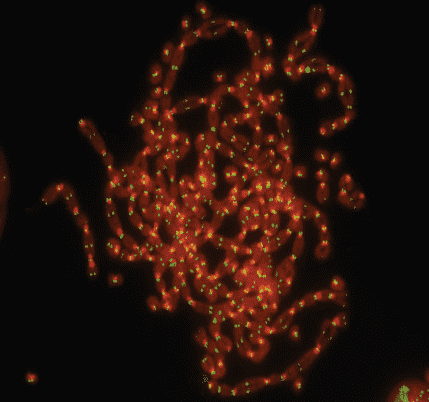

- The (new) telomere theory of aging – April 15, 2023

Yamanaka factors

In 2012, Shinya Yamanaka and John Gurdon were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for the discovery that mature somatic cells can be converted to stem cells by introducing just four transcription factors (Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc). These so-called induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have properties that are very similar to embryonic stem cells; that is, they can be turned into any specialized somatic cell, such as a skin cell or a heart cell.

However, for our purpose here, the most interesting feature of iPSCs is that the age of these reprogrammed cells is reversed. For instance, according to the current most accurate aging biomarker, the Horvath clock, the age of iPSCs is essentially 0. Likewise, the telomere length is restored as well.

Rejuvenation procedure

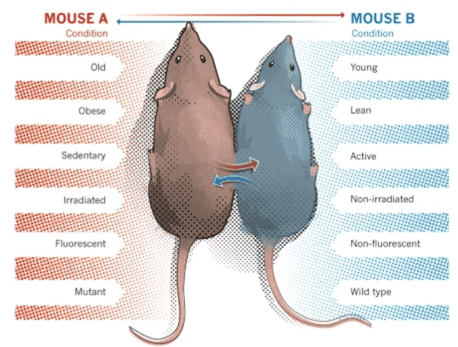

David Sinclair (and others) want to use this remarkable feature of iPSCs to reverse the age of cells not only in vitro but also in vivo, that is, in multicellular organisms. Obviously, you can’t just turn specialized cells into stem cells in a living organism. If you turn a heart cell into a stem cell, it can no longer do its job in the heart and instead will cause cancer. However, Sinclair believes that it is possible to avoid this problem by working with a subset of the Yamanaka factors (without c-Myc) and by limiting the reprogramming time.

The rejuvenation procedure that Sinclair proposes works like this:

- With the help of an engineered adeno-associated virus (AAV), the DNA of all cells receive new genes (a combination of the Yamanaka factors). However, these genes are inactive at first.

- In addition to the Yamanaka factors, a failsafe switch is inserted that allows the activation of the Yamanaka factors by administering a certain molecule, such as doxycycline.

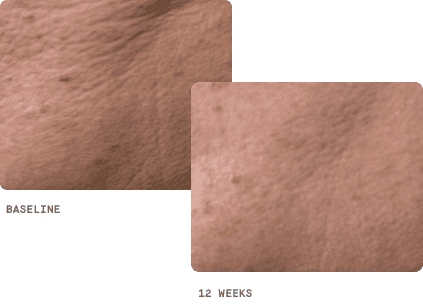

- To start the rejuvenation process, doxycycline is given for a certain time. This activates the combination of the Yamanaka factors, which reverses the age of all cells without turning them into stem cells. After this, the treatment with doxycycline is discontinued.

- The rejuvenated cells restart the aging process. Thus, after the cells reach a certain age, you must take doxycycline again.

This sounds like science fiction; however, the technologies used (iPSCsC technology gene therapy and controlled gene expression) are not really that new and are more or less well established. What’s new is to use this combination of these technologies for reversing the age of multicellular organisms. In fact, Sinclair’s team successfully applied these technologies in the optic nerves of aging mice to restore their vision and Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte was even able to prolong the lifespan of mice.

Reprogramming of cells in living tissue cries for cancer because even if it is possible to prevent somatic cells from turning into stem cells, errors during reprogramming in a small number of cells should significantly increase the likelihood of further mutations that eventually cause cancer.

However, through fine-tuning of the procedure, the risk can probably be lowered. With the rapid progress in cancer research thanks to recent advances in cell biology, new treatments such as immunotherapy will probably eliminate the terror of cancer in the not-too-distant future.

Yamanaka and Sinclair’s theory of aging

I was a little surprised to find that Sinclair believes cell reprogramming is the most promising approach to finding a cure for aging. His information theory of aging claims that information loss in the epigenome caused by the wear and tear of the repair processes that fix double-strand breaks in DNA leads to the loss of cell identity and cellular dysfunction. If the reprogramming of cells can reverse their age, this information cannot be lost entirely because the information is required to restore the epigenome to its original state.

Sinclair is quite aware of this problem. He solves this contradiction by claiming that cells have a “backup” of the epigenome, or what he calls “a biological correction device” (with reference to Shannon’s information theory). Let me quote this because I believe this the most crucial part of Sinclair’s theory (David Sinclair, Lifespan: Why We Age―and Why We Don’t Have To, pp. 169–170):

If adult cells in the body, even old nerves, can be reprogrammed to regain a youthful epigenome, the information to be young cannot all be lost. There must be a repository of correction data, a backup set of data or molecular beacons, that is retained through adulthood and can be accessed by the Yamanaka factors to reset the epigenome using the cellular equivalent of TCP/IP. What those youth markers are, we’re still not sure. They are likely to involve methyl tags on DNA, which are used to estimate an organism’s age, the so-called Horvath clock. They likely also involve something else: a protein, an RNA, or even a novel chemical attached to DNA that we haven’t yet discovered. But whatever they are made of, they are important, for they would be the fundamental correcting data that cells retain over a lifetime that somehow direct a reboot.

I must have read several thousand pages about cell biology in the last few years, and I’ve learned that many amazing things happen down there at the cellular level. However, the claim that the epigenome stores a backup of its original state in the epigenome (methyl tags, unknown chemical attached to DNA, etc.) deeply confused me because it contradicts everything I understood about the cellular development processes.

Puzzling questions for Sinclair

In the philosophy of science, we would call this the introduction of hidden variables. An obvious contradiction between a theory and empirical data is explained away by referring to hidden processes that have not yet been discovered. This most famously happened when physicists were unable to accept the probabilistic nature of quantum physics. Einstein wasted a lot of time trying to find these hidden variables (because God does not play dice).

Of course, this doesn’t mean that Sinclair’s hidden backup device doesn’t exist. However, his claim about the existence of a correcting device raises more questions for me than it answers:

- If aging is information loss in the epigenome and the backup is also stored in the epigenome, why is this backup information not affected by the wear and tear of DNA repairs? Or, in other words, why doesn’t the backup lose information to entropy but the rest of the epigenome does?

- We already have a theory (although not well-established) that explains how reprogramming works in early embryogenesis and gametogenesis. For instance, after a sperm cell fertilizes an ovum, DNA demethylation first removes the methyl tags and then de novo methylation adds the methyl groups in a precisely programmed way. It is mostly DNA (through transcription factors), signals from other cells in the organism, and environmental factors (and not some epigenomic backup device) that control cell differentiation and therefore the structure of the epigenome. So why would this be any different with iPSCs? Obviously, the Yamanaka factors exist for a natural reason. Without the ability of cells to reprogram and reverse their age, life could not exist because all cells have progenitors that lived millions or even billions of years ago. Thus, cells must be able divide into daughter cells with age 0 because otherwise offspring would be born with the same biological age as their parents.

Yamanaka and the wear and tear theory of aging

Even more puzzling to me is that any theory that claims the wear of tear of metabolism causes aging could survive after Yamanaka’s discovery. What happened to all the oxidative and free radical damage to DNA, epigenome, mitochondria, proteins, and lipids? How can just four transcription factors (or three, for that matter) repair all this damage that has been accumulated in decades in the blink of an eye? In fact, all wear and tear theories of aging need a myriad of Sinclair’s backup devices to restore all the damaged cell ingredients to a youthful state during reprogramming.

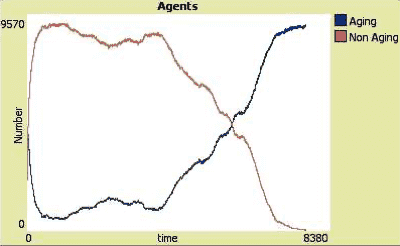

On the other hand, if reprogramming decreases age, why not simply assume that the age of cells increases over time due to programming? If aging is a programmed process accompanied by all the other programming that happens during cell differentiation, no hidden backup device is needed. Aging, therefore, would then be just the programmed change of gene expression patterns. Sounds crazy? Not if you admit that aging has an important function in biological evolution.

Note that the damage theory of aging contradicts a variety of empirical findings. A good summary can be found in this article.

Conclusion

What I really like about Sinclair’s book is that he at least addresses the problems that his theory faces. Many other scientists who believe in the wear and tear theory seem to simply ignore the contradicting evidence. The fact that an advocate of the wear and tear theory feels the need to introduce hidden variables, is a god sign that we are on the verge of a paradigm shift in geroscience. The good thing is that Sinclair’s research does not seem to be determined by his theoretical views. Instead of actively searching for his correcting device, he focuses on reprogramming instead. In the end, it doesn’t really matter if Sinclair’s information theory of aging is correct or not, as long as he finds a way to program the right age into our cells.

Terrific article

Eugene, thanks!

Mike, I just tweeted about your article, and how it seems to contradict the latest big story in MIT Tech Review about Altos Labs…

https://twitter.com/eugediana/status/1434987422425698305?s=20

please correct me if I’m wrong I’d really appreciate it…

Eugene

I read the article, but didn’t have the time yet to read the preprint paper. Where do you see a contradiction?

If you look at my tweet I point it out w/2 pics

Please formulate your argument here. In what way does my article contradict this paper?

OK sure.

MIT: “One problem is that reprogramming doesn’t just make cells act younger but also changes their identity—for instance, turning a skin cell into a stem cell. That is what makes the technology too dangerous to try on people yet.”

hplus: “To start the rejuvenation process, doxycycline is given for a certain time. This activates the combination of the Yamanaka factors, which reverses the age of all cells without turning them into stem cells. After this, the treatment with doxycycline is discontinued.”

the issue is whether reprogramming changes the identity of cells–that seems to me to be the contradiction…

happy to hear your feedback, thank you much!

Eugene

hplus:

So I discussed the exact same problem. Sinclair and Belmonte proved that it can be done in vivo. But Ocampo is certainly right when he says that it is a risky procedure and it remains to be seen if this technology can be used in humans. So no contraction.

Ok, thanks again…I just had gotten the impression, from the MIT piece, that cell reprogramming by definition turns the cell into a stem cell, but in fact you pointed out that they’ve avoided doing this, so it seemed like they missed that very-important point. But I guess writing popular articles for new science can be a challenge to please all people 🙂

I’m mostly excited about Altos but I know popular science articles about Aging in particular are not normally looked-upon as helpful by those same scientists necessarily, for various reasons (like hype, or snake-oil, eternal dictators, sisyphus, etc).

Yeah, that was the idea when Yamanaka found those four transcription factors. He didn’t even think of using them for rejuvenation. But later it turned out that rejuvenation and inducing stemness are two different processes. This makes sense because both processes are probably relatively complex and different enzymes are needed to get the job done. The Yamanaka factors trigger a cascade of events and once we understand the details of these processes it might be possible to control the rejuvenation part more reliably without risking turning differentiated cells into stem cells.

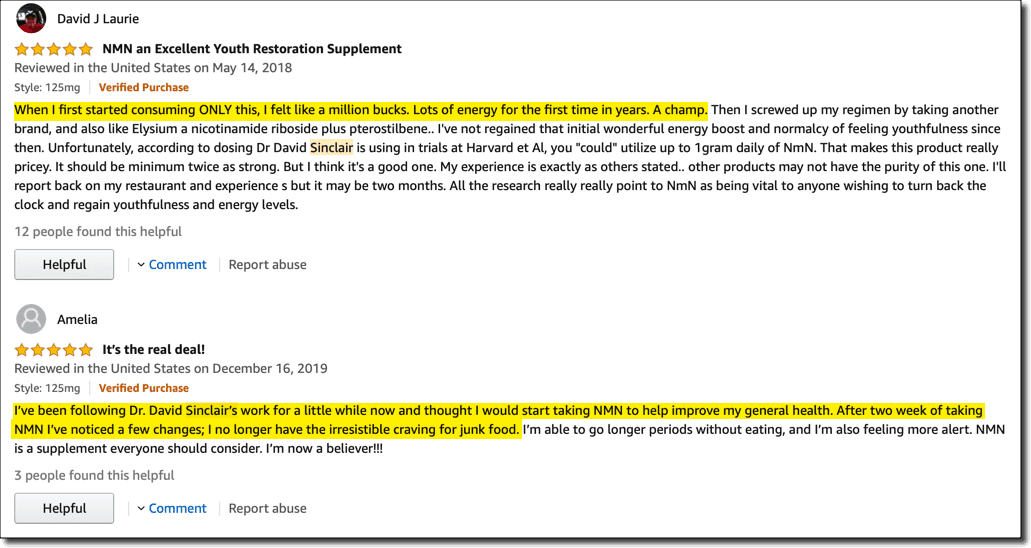

It’s a great article and your questions are good questions. What it demonstrates is that Sinclair doesn’t understand epigenetics. What does “the cellular equivalent of TCP/IP” even mean? Most legitimate scientists are highly skeptical of Sinclair’s work, as they should be, and I think, frankly, that he’s causing considerable harm by endorsing junk science and misleading the public.

I agree that this idea that the epigenome stores information in an analog form doesn’t really make sense. It appears to me that Sinclair confuses the distinction between analog/digital and continuous/discrete. It is a common misunderstanding, but a Harvard professor should know better even if this is not his field of expertise. Besides, methyl groups are either attached to the DNA molecule or not. Thus, we have a clear case of “discrete” here.

Perhaps the winding of DNA strands around histone proteins can be seen as “continuous.” However, down there at the molecular level quantum effects already come into play and we realize that “continuous” is an illusion anyway.

Originally, I planned to write an article about this topic, but I guess nothing interesting about aging could be learned here. As far as I know, nobody in the geroscience community picked up this view that the epigenome is analog.

Great article! Another explanation is that aging is the maladapted continuation of normal organism development, i.e. the organism needs changing gene expressions as it grows into adulthood, and needs a mechanism to control this change. The mechanism, however, doesn’t stop once the organism reaches a certain age, because it was not selected for that, given that the majority of reproduction happens before that age.

Riccardo, thanks! I think the view that reproduction is supposed to happen at a certain age is flawed. If evolution is is really only about maximizing reproduction, evolution would ensure that reproduction happens at any age.

Reproduction needs to happen at a certain age because organisms die, not from aging, but from other causes and then they can’t reproduce. One example is that pygmy people were selected to mature earlier (and thus reach a smaller height) because of the high mortality and low life expectancy they experience.

I don’t see it as a coincidence that the age at which aging starts to be deleterious is around the life expectancy of early humans (~30 years). The clock works fine until then, but after that most humans would die from predators or disease or something else and thus there would be no selective pressure for the clock to continue working.

I heard this argument many times and I find it very implausible. What about the large number of organisms that are not killed by predators? Why wouldn’t evolution make sure that they continue reproducing until they are eventually killed?

What large number? If life expectancy was around 30y that’s the average age of death. I haven’t found a model of the distribution but I’d expect very few to reach more than 50 years. Moreover it’s not clear early humans could afford to have multiple sequential children. If you have a child at 30 you need to survive until 45 to help it reach adulthood, otherwise it’s useless, and maybe that nearly never happened. Sexual selection could also come into play with humans favoring younger.

Though I’ve read the other post about aging being programmed to ensure innovation and it does make sense.

I don’t think that the average age of death matters. As long as there are some individuals that are not killed by predators, it would makes sense that they keep reproducing until they are killed.

The average human age of the past was 30 because of high infant mortality, not because people died at age 30. Life expectancy was up to mid 60’s assuming they avoided death in childhood. Some cultures still have a tradition of their elderly wandering off into the woods/ arctic to die rather than burden the tribe.

Offspring doesn’t just take advantage of their aging parents and grandparents because of resource savings. Another important biological function of aging is that the old serve as food for predators. This is probably the main reason why many species age slowly instead of just dropping dead in the woods after reproduction. Because predators always go after the weakest members, aging greatly improves the survival chances of the very young in the group. Yes, this is how mother nature arranged things for us on this beautiful planet.